A Mirror for Humanity: Why the Cardassians are Trek’s Best Alien Race

In the Season 4 episode of Enterprise entitled “The Forge”, there is a wonderfully insightful conversation between the Vulcan Ambassador to Earth, Soval and Admiral Maxwell Forrest of Earth’s Starfleet.

Soval: “We don’t know what to do about Humans. Of all the species we’ve made contact with, yours is the only one we can’t define. You have the arrogance of Andorians, the stubborn pride of Tellarites. One moment you’re as driven by your emotions as Klingons, and the next you confound us by suddenly embracing logic!”As much as those qualities define humanity, they also define the Cardassians as well, who are arguably the most compelling alien race in Star Trek because they serve such a striking parallel to much of human history, both past and present. And in doing so, they act as a cautionary tale about the dangers of our own species’ internal demons.

Forrest: “I’m sure those qualities are found in every species.”

Soval: “Not in such confusing abundance.”

When you consider the other main alien races within the Trek universe, they don’t compare to the type of consistent characterization and development that the Cardassians received. The Andorians and the Tellarites, first seen in The Original Series episode “Journey to Babel”, are not seen again until Enterprise (if we’re not counting The Animated Series), and even then, we as the audience don’t know that much about them outside of a handful of admittedly wonderful episodes. The Vulcans, surprisingly enough, also fall into this paradigm. Although a Vulcan is the most iconic alien being in all of Trek (in the form of Spock), outside of select scenes from the movies and a handful of episodes from The Original Series and Voyager, the audience doesn’t learn that much about Vulcan culture or society until Enterprise. And although we do learn a lot about Vulcans from that series, particularly how they used to be very much like humans in the past, the fact that they’re in a more evolved and advanced state from humanity takes away from their ability to act as a parallel to our lives now. The Romulans, like their Vulcan cousins, are often referenced in Trek canon, but from what we see of them in terms of characterization and development is often more one-dimensional in nature. The Klingons, probably the most well-known of the Trek races, certainly don’t suffer from a lack of screen time, on television or in the movies. But with a few exceptions, they are also one-note and archetypical in characterization, especially in The Next Generation era. The Bajorans, on the other hand, do not fall into this paradigm. First introduced in TNG and later in Deep Space Nine, they are admittedly well-drawn both as a culture and as a society, particularly regarding their faith and spirituality. But speaking for myself, the Cardassians are more compelling due to their unique and tragic narrative denouement, something that the Bajorans lack. Cardassia ultimately endures a fate that is akin to the greatest of Greek tragedies and in doing so, truly acts as a cautionary tale for all of humanity.

A Cardassian delegation aboard the Enterprise-D

One of the first things that jump out to long-time fans of the

franchise is the fact that the Cardassians didn’t have an origin based

upon The Original Series. They were the relative newcomers to

the galactic neighborhood, having been introduced in the third season

TNG episode “The Wounded”. From their first portrayal here to their

eventual role as the primary antagonists in Deep Space Nine,

the Cardassians were conceived with the idea that they were going to be

more three-dimensional than previous alien races. The episode’s

director, Chip Chalmers noted “We

introduced a new enemy that’s finally able to speak on the level of

Picard. They’re not grunting, they’re not giggling, they’re not mutes or

all-knowing entities. Here are the Cardassians who also graduated first

in their class and they’re able to carry on highly intelligent

conversations with Picard, but they’re sinister as hell. It was fun to

introduce a whole new alien race.” In this episode, we see the critical

seeds of the more well-known aspects of the Cardassian mindset being

planted: their militarism, their inherent suspicion of outsiders, and

their penchant for duplicitousness and strategic maneuvering. Indeed,

for Cardassia, the only instrument that can ensure order and security is

a strong Nation State bound by common purpose, force of arms, and an

unwavering sense of right and wrong that can ward off its enemies, both

internal and external. In order to ensure the State’s survival, two

institutions were key in Cardassian society: the military in the form of

the Central Command and the intelligence and internal security

apparatus in the form of the Obsidian Order.

Gul Dukat of the Central Command and Garak, formerly of the Obsidian Order

However, it is important to remember that

although a strong militaristic ethos has always infused Cardassian

culture, the entire race is not uniformly depicted as such. A number of

portrayals do indeed add much needed texture and nuance in this regard.

For example, in the season three DS9 episode titled “Destiny”, there is

a marvelous portrayal of Cardassians that have other career paths than

ones that aspire to be a glinn, gul, or even legate in the Central

Command. As civilian scientists, Ulani Bejor and Gilora Rejal

demonstrated that not every Cardassian necessarily desired to join the

military or intelligence ranks. Furthermore, as female members of their

race, they were able to provide texture and nuance about larger

Cardassian gender dynamics, most notably around the idea that since

females were perceived to be smarter than their male counterparts, they

would naturally gravitate towards the sciences, whereas the males would

often be inclined towards “less” intellectually rigorous pursuits such

as the military and politics. It’s a shame that the DS9 writers didn’t

carry this fascinating idea forward because it serves as a reverse

mirror of our own society and how women are still underrepresented in

STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields today.

It was even shown that consummate career military officers, such as Gul

Dukat and Gul Madred, also had interests and passions for art,

archaeology, philosophy, history, and other intellectual pursuits. There

existed a Cardassian Institute for Art and an entire art movement on

the homeworld called “The Valonnan School” that ostensibly emphasized

impressionistic art. There were entire genres of diverse Cardassian

literature that ranged from serialistic poetry to repetitive epics and

enigma tales. And perhaps most telling, there even existed a Cardassian

underground dissident movement, comprised of academics, scholars, young

people, and other idealists, who opposed the stranglehold that the

Central Command and the Obsidian Order had on Cardassian society and

sought to restore the power of the civilian-led Detapa Council.

Two female Cardassian scientists, Ulani Bejor and Gilora Rejal

Through nearly all of these unique manifestations of Cardassian

culture and thought, there is a singular theme that runs through them:

the idea that individual needs are subordinate to the collective good of

Cardassia. At the heart of this idea to promote the collective good

lies the family. Indeed, in the second season DS9 episode “Cardassians”,

Kotan Pa’Dar noted that “We care for our parents and our children with

equal devotion. In some households, four generations eat at the same

table. Family is everything.” Thus, it should come as no surprise that

someone such as Elim Garak would consider “The Never Ending Sacrifice”, a

literary epic focusing on seven generations of citizens devoted in

service to the State, to be the “finest Cardassian novel ever written”.

This creed is in essence a variation on the theme that Spock espoused in

“The Wrath of Khan” and would later become an informal ethos for the

Federation, and by extension humanity: “The needs of the many outweigh

the needs of the few”. But as evidenced by humanity’s own history, such

an ethos can be manipulated and perverted to justify unspeakable crimes

and atrocities and Cardassian history is no exception.A striking example of how this desire for the collective good can be used for terrible ends is witnessing how the Cardassian judicial system operates. In the second season DS9 two-part episode “The Maquis”, Dukat lays out to Commander Sisko its underpinnings:

SISKO: They’ll be tried for their crimes under the Federation Code of Justice.

DUKAT: And if they’re found innocent?

SISKO: I doubt that they will, but if they are, they’ll be set free.

DUKAT: How barbaric. On Cardassia, the verdict is always known before the trial begins. And it’s always the same.

SISKO: In that case, why bother with a trial at all?

DUKAT: Because the people demand it. They enjoy watching justice triumph over evil every time. They find it comforting.

SISKO: Isn’t there ever a chance you might try an innocent man by mistake?

DUKAT: Cardassians don’t make mistakes.

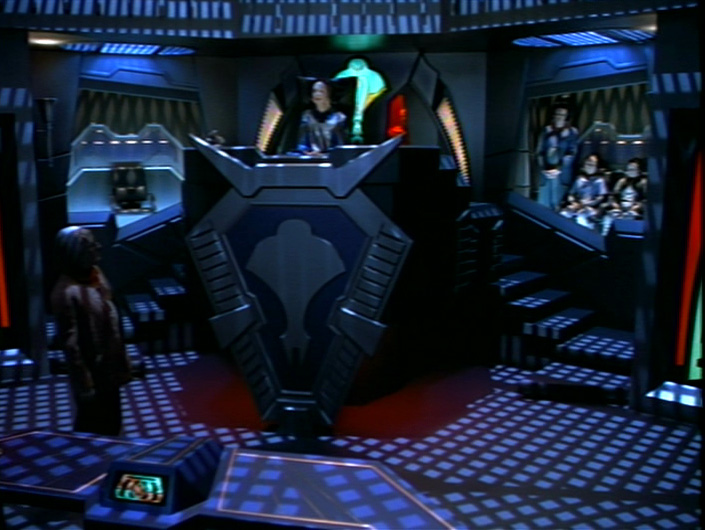

A Cardassian trial is publicly broadcast

Thus, in the view of Cardassian

jurisprudence, the individual rights of the accused to face their

accuser and the presumption of innocence is completely irrelevant. Their

entire concept of justice is precisely inverted from our own in order

to vindicate the State, its prosecution, and its methodology in reaching

a guilty verdict because it is simply inconceivable that the State, in

its effort to promote the collective good, could ever be wrong. In the

penultimate episode of that season entitled “The Tribunal”, we see in

vivid detail how Cardassian justice is implemented. The following

exchange between Miles O’Brien and his state appointed counsel in that

episode is particularly revealing.

O’BRIEN: I’ve been told that I’ve already been charged, indicted, convicted, and sentenced. What would I need with a lawyer?

KOVAT: Well, Mr. O’Brien, if it sounds immodest of me I apologize, but the role of public conservator is key to the productive functioning of our courts. I’m here to help you concede the wisdom of the state.

Kovat “defending” O’Brien before the Cardassian court

The very title of the state appointed

counsel, “public conservator” illustrates the extent to which Cardassian

justice is conservative in nature and only seeks to uphold a presumed

incorruptible status quo. Such proceedings are then broadcast to the

citizenry and to young children in particular in order to strengthen

their belief and faith in Cardassian institutions and to provide a

cautionary example that criminals in Cardassia are always guilty and

should only seek the mercy of the court. This dual imperative of

breaking the will of the presumed guilty and showing a younger

generation the wisdom of such a process is demonstrated masterfully in

TNG’s sixth season two-part episode “Chain of Command” when Madred not

only invites his young daughter to the room where he is torturing

Captain Picard, but also when it is shown that breaking Picard’s will

into recognizing “five lights” is what ultimately mattered to him,

instead of any Federation military secrets. Such a portrayal is a vivid

and poignant reminder of the show trials, witch hunts, and inquisitions

that have marred our own history when governments and regimes have used

such dubious tactics in the pursuit of their own definition of

“justice”.

Gul Madred bonding with his daughter, with a tortured Picard nearby

The greatest manifestation of how the pursuit of the collective good

can be perverted into something terrible is how the Cardassians acted in

their dealings with the Bajorans and the Maquis. First introduced in

the TNG Season 6 episode titled “Ensign Ro”, the Bajorans were a race

that had been subjugated by the Cardassians forty years prior in a grand

colonization effort, beginning in 2328 and ending in 2369. During this

decades-long period known as “The Occupation”, Cardassians engineered a

systematic and coordinated campaign of strip-mining, forced labor, and

genocide to control, dominate, and exploit the people and physical

resources of Bajor. Those that could escape the devastation being

wrought on the surface of Bajor would relocate as refugees throughout

the galaxy. And many others would also take part in the Resistance, an

organized effort by the Bajorans using whatever tactics (guerrilla,

terrorist, or otherwise) to force the Cardassians to withdraw from their

homeworld. The Bajorans would eventually succeed in this goal, as seen

in “Emissary”, the pilot episode of Deep Space Nine. However,

the moral compromises the Bajorans had to make in order to achieve this,

when taken into context with the harsh conditions imposed by Cardassia,

is a striking and sobering commentary on our own current

socio-political issues of displacement, resistance, terrorism, and

occupation. And this was achieved because it was always intended to

serve such a purpose. Producers Michael Piller and Rick Berman at the

time noted that

“The Bajorans are the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization), but

they’re also the Kurds, the Jews, and the American Indians. They are any

racially bound group of people who have been deprived of their home by a

powerful force”, who in this case was the Cardassian Empire.

A Cardassian guard closes a gate on Bajoran slave workers

They added, “When you talk about a

civilization like the Bajorans who were great architects and builders

with enormous artistic skills centuries before humans were even standing

erect, you might be thinking a lot more about Indians than

Palestinians.” The parallel to the historic plight of Native Americans

is especially poignant because it deals directly with another fractious

relationship the Cardassians had, this time with the Maquis: Federation

colonists who were displaced by the new borders established by the

Federation’s peace treaty with Cardassia and refused to leave their

homes. They eventually adopted the name “Maquis”, a term dating back to

the French underground resistance to the Nazis during the Second World

War. The original concept behind the Maquis was conceived of in TNG’s

Season 7 episode entitled “Journey’s End”, which featured descendants of

Native Americans resettling on a Federation colony near the Cardassian

border only to face the threat of forced relocation. The Maquis would

eventually come to encompass many other Federation settlers caught

behind these new borders, as well as disaffected and disillusioned

Starfleet officers who felt that the Federation had sold out its own

citizens to appease a duplicitous and aggressive adversary.

Consequently, the Maquis would actively engage in insurgent and

terrorist actions against both the Federation and the Cardassians in

defense of their “independent nation”.

The Maquis and the Cardassians, locked in battle

Cardassian actions to stamp out both the Bajoran and Maquis

resistance were cruel, brutal and unrelenting. The Empire’s desire to

secure its own collective good at the expense of others would lead to

the use of harsh and brutal tactics that often precipitated the use of

such tactics in return and perpetuated a bitter cycle of violence. The

irony is that these tactics were ultimately counter-productive for

Cardassia. Bajor won its independence regardless and the Maquis

stubbornly refused to be suppressed. As we have witnessed, there is

nothing more dangerous than a national ego that has been bruised. It has

spawned two world wars in our own recent history, and countless other

conflicts in the past. Cardassia, stinging from its own self-perceived

weakness in dealing with the Bajorans and the Maquis and only

exacerbated by its recent military losses to the Klingons, would

eventually make the ultimate deal with the devil. Under the sway of a

charismatic leader in the form of Gul Dukat, Cardassia joined the

Dominion with grand notions of renewed patriotism and restored glory.

However, none of this would come to pass. Instead, Dukat’s actions would

help plunge the entire Alpha Quadrant into a war that would ultimately

leave Cardassia completely broken and its people devastated, with over

800 million of its own citizens dead at war’s end.

Gul Dukat leading Cardassian and Jem’Hadar forces under the banner of the Dominion

Throughout the broad strokes of Cardassian society and culture, it’s

evident we can see so many parallels to our own history. As we ourselves

have witnessed, the appeal of patriotism, self-pride, the rule of law,

the security of order, and the desire for the collective good are all

powerful and beneficial motivators. But they can also be corrupted,

manipulated, and exploited to justify unspeakable acts in the name of

ensuring and preserving those very same things. But the most important

aspect of a mirror is how it reflects everything, both the good and the

bad. Thus, the most vital component of the Cardassian mirror for

humanity is one that actually represents redemption. And in the grand

story of Cardassia, there is no other person that better represents

redemption than Damar.

A younger Damar as the model Cardassian soldier

Initially only introduced as a tertiary

character and one that was little more than a background henchman for

Dukat, the character of Damar eventually became the embodiment of the

entire Cardassian people. As the ultimate archetype of a true patriot,

he believed that everything done in the name of Cardassia was worth

doing and he personally relished in the brutal excesses and military

conquests of the State. But only near the end, when he realized what a

terrible cost such an attitude inflicted, both on his people and to him

personally, Damar became the catalyst for the Cardassians to openly

rebel against the Dominion. In doing so, he helped his people break free

from the centuries-long cycle of aggression that had finally brought

their society to ruin. And much like the symbols of our own history who

became martyrs in defense of a greater ideal, Damar’s death in defense

of the idea that Cardassia could choose its own fate, one that was no

longer driven solely by aggression, was not only his attempt at personal

redemption, but also redemption for his entire civilization.

Damar leading the rallying cry of rebellion against the Dominion

The ruins of Cardassia Prime following the war

When everything said is done, I can’t think

of a greater example of a more powerful allegory in Star Trek than the

ones told about the Cardassian people. It contains every element of

humanity’s own ugly past and present, touching everything from torture,

terrorism, slavery, genocide, colonialism, and xenophobia, all terrible

acts that unfortunately still haunt us today. But it also balances out

this portrayal by showing a race that is not solely defined by these

actions. The Cardassians weren’t just fierce prideful warriors, they

were passionate poets and writers, talented artists, brilliant

scientists, and insightful philosophers as well. And they were also

fathers, mothers, sons, and daughters. In providing such a rich milieu

of depth and complexity, the Cardassians are in my opinion the best and

most compelling alien race in Star Trek. And in the process, they act as

the perfect mirror for humanity, reminding us to always be vigilant

against our own internal demons, lest they destroy all of us as well.

Addendum: For those that wish to continue the epic tale of the Cardassians, I highly recommend the excellent Star Trek books of Una McCormack, which can be found here. Known around Trek literary circles as “The Queen of Cardassia”, Ms. McCormack uses her background as a sociologist to further build the world of the Cardassians, particularly in chronicling their struggle and triumphs following the devastating Dominion War.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario